NEWS

IN BRIEF

As Pakistan’s cities buckle under growing population pressures, the answer to smarter urban living doesn’t lie in more concrete; it lies in data and design. In cities like Beijing and Singapore, real-time information fuels responsive systems: subways adapt to surges, traffic lights shift with congestion, and public services evolve through citizen feedback. These are not just feats of technology; they are products of deliberate design thinking that puts human needs at the center.

Pakistan has the raw ingredients: high mobile penetration, emerging transit systems, and a tech-savvy youth, but lacks the connective tissue of data integration and user-centered problem-solving. This blog explores how pairing data science with design thinking can help Pakistan leapfrog traditional development paths, turning fragmented systems into intelligent networks that listen, learn, and serve. The future of our cities depends not only on what we build, but on how deeply we understand the people who move through them.

SHARE

In Beijing, a city of roughly 22.6 million people, managing crowding is a daily imperative. (For perspective, that’s on the same order as one-sixth of Pakistan’s most populous province: Punjab, which has ~127.7 million people. Over the years when I lived in Beijing as a masters scholar, I watched city planners layer intelligent infrastructure on top of this pressure. Ubiquitous sensors, cameras and mobile apps feed powerful computer systems that constantly monitor and optimize the flow of people and vehicles. Where traffic once ground to a halt, now AI-driven “City Brain” platforms adjust traffic lights in real time; where crushes threatened subway concourses, digital twins and smart turnstiles help smooth the stream of riders. These measures from live transit data to crowd-control AI give Beijing’s government a real-time “pulse” on the city and the agility to respond quickly.

Beijing’s subway stations and roads technology monitors traffic and crowd density in real time. For example, Beijing’s subway system (22 lines, with over 10 million riders on an average weekday) is embedded with cameras and sensors. The city’s transit operator even piloted facial-recognition cameras and palm scanners at entry gates to speed commuters through turnstiles during peak hours. Underneath these smart gates and overhead screens are data streams: turnstile counts, CCTV video and mobile ticketing logs feed a central monitoring hub. In one line (Beijing’s Line 6) engineers have built a “digital twin” – a virtual replica of the entire subway line that ingests live sensor data. This digital twin can simulate delays or crowd surges off-line so planners can test solutions before applying them in the real system. The result is more reliable schedules and fewer unexpected bottlenecks.

In practice this means daily adjustments. Beijing’s operations center uses AI models to study human movement: predicting which stations will overflow and when, and rerouting trains or deploying staff accordingly. Trains are added or held as algorithms analyze weather forecasts, holiday travel patterns and even major events. Mobile apps (via WeChat or Alipay) let commuters see live crowding levels on each platform and suggest less-congested routes. Some stations test smart fare gates that automatically swing open faster when many people approach, reducing crushes at rush hour. In emergencies, this data-driven system also aids passenger safety: for instance during the COVID-19 outbreak Beijing deployed AI-powered infrared cameras in some subway stations (by firms like Megvii and Baidu) to screen passengers’ body temperatures and mask compliance. In short, everything from ticket purchases to train traffic is captured by software so that planners “see” and manage crowds as they form.

Meanwhile on the surface, traffic control in Beijing has gone similarly high-tech. Under Alibaba’s City Brain initiative (first piloted in Hangzhou in 2016), many Chinese cities now pipe live camera feeds, GPS and telecom data into an AI. In Hangzhou, for example, City Brain took over 104 traffic-light intersections and boosted vehicle speeds by about 15%. In Beijing today, this means smart traffic lights that adapt to conditions: if one road is jammed, connected signals give extra green time to clear it. The system also spots accidents or stalled cars on camera feeds and alerts authorities automatically. The net effect is fewer gridlocks and quicker emergency response. Altogether, China’s large cities are stitching together buses, metros, taxis and even highways into one integrated transit web. Commuters can plan a trip across modes (metro to intercity train to city bus) on a single smartphone app, while the system adjusts routes and schedules in real time based on demand. The result is a mobility network that learns and reshapes itself. In Beijing this data-centric approach, backed by hundreds of millions of smart devices, is what keeps daily city life moving smoothly despite the population pressure.

While China’s scale and tech prowess are impressive, there is another country which offers a model that is both efficient and deeply people-centered. As part of its “Smart Nation” strategy launched in 2014, Singapore has integrated data analytics, IoT, and design thinking across urban life from transportation to healthcare to housing. What sets Singapore apart is its deliberate blend of citizen-centric innovation with real-time data.

Take “OneMap”, for instance, a unified geospatial platform that aggregates everything from footpath data to school zones, bus stop usage, and WiFi coverage. Planners use it not just to model infrastructure but to prototype ideas and simulate citizen behavior. For instance, before building new MRT (metro) lines, Singapore’s Urban Redevelopment Authority uses anonymized mobile data to study commuter flows, test alternative routes virtually, and gather feedback from citizens using immersive dashboards. A standout example is MyResponder, a mobile app that alerts trained volunteers when someone nearby is experiencing a cardiac emergency. It works because real-time geolocation data is shared within defined privacy bounds and the application development followed design thinking principles: interviewing emergency responders, testing early versions with users, and iterating based on feedback. Today, it has saved hundreds of lives and sparked similar efforts in traffic response and flood.

How Pakistan’s Cities Compare

Back home, Pakistan’s experience with big-data urban planning is still nascent. We have started building new transit lines and highways notably Lahore’s Orange Line Metro but the data feedback loops are largely missing. For example, Lahore’s Orange Line has achieved around 178,000 daily passengers at present. More importantly, Pakistan’s systems run mostly on fixed timetables and manual control. The Orange Line is managed from a central control center, but trains run on rigid schedules; ridership numbers are collected for reporting, not used to dynamically adjust service. By contrast, in Beijing each delay or surge is tracked live so trains can be dispatched on the fly.

In road traffic, too, we lag. Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city has well-documented congestion, but real-time smart signaling is still an aspiration. To be sure, Karachi’s Safe City project (launched in late 2024) has installed hundreds of surveillance poles and cameras (over 157 poles with live feeds, 100 cameras actively monitored as of November 2024). These improve security, but they haven’t yet translated into an integrated traffic-management network. Most lights in our cities still operate on fixed timers, and authorities respond to jams only after they form. Lahore has a “Smart City” traffic control room and some journey-time sensors, but it has not rolled out the kind of AI-driven adaptive signaling seen in China and Singapore. Even in new planned communities (e.g. Islamabad’s well planned sectors or the blueprint for “Smart Cities”), the vision of live data streams guiding everyday operations is mostly on paper.

I say this not to shame our planners, but to underscore a gap: we have missed opportunities to use the data we generate. Pakistanis carry smartphones (over 75% mobile penetration nationwide), generating GPS and traffic data. We have banks that collect payments electronically (Digital payments grew 30% in 2023 in Pakistan). Our emerging metro bus systems and ride-hailing apps could feed transit data to a public platform. Yet the culture of openly using that data is weak. We’re still building stations and roads first, rather than first seeking to deeply understand commuter patterns and pain points via data. For instance, Lahore’s planners know a large portion of orange-line riders head downtown, but they lack a continuous real-time heatmap of station crowding. Karachi’s police cameras see traffic bottlenecks on TV screens, but the signals don’t yet auto-adjust to relieve them.

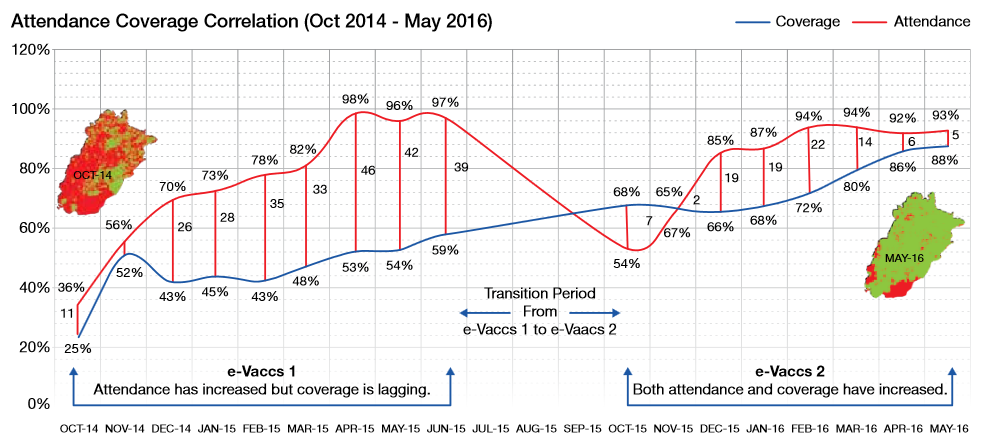

In short, we rely on reactive fixes rather than the kind of real-time, data-driven problem-solving we see in and Singapore. That said, there are sparks of progress. Lahore has begun publishing some metro ridership stats (albeit infrequently). Some city bus routes in Islamabad and Karachi are monitored by basic GPS (for public awareness, if not yet for AI optimization). There are promising successes from the health sector especially with e-Vacc, an Android app used by field vaccinators to upload geo‑tagged vaccination records in real time. District authorities and partner agencies access dashboards and heat maps highlighting vaccination coverage, refusal cases, zero‑dose areas, and missed children. These visuals helped supervisors focus outreach on underserved pockets and drove geographical coverage from ~25% in 2014 to ~88% in 2016.

These are small steps. The current state is fragmented, not integrated. We do have homegrown talent in data science and a young population eager for tech-led solutions. But without a deliberate strategy to harness urban data, much of this potential goes untapped.

From Data to Action: The Power of Design Thinking

So how can Pakistan bridge the gap? The answer lies in pairing data science with human-centered design. Data alone is just raw input, it needs a creative process to turn it into solutions people will use. This is where design thinking comes in. In essence, design thinking is a structured, iterative approach that starts and ends with the user. As one innovation report explains, design thinking “puts the user at the center,” using deep empathy, listening, rapid prototyping and constant iteration. In practical terms, it means beginning any solution by walking in the citizen’s shoes: what does a commuter, driver or patient truly need? You gather qualitative insights, perhaps some interviews, on-the-street observations, to complement the quantitative data. Then you reframe the problem: perhaps the issue isn’t “build a new road” but “people need an affordable, clean, rapid way to commute downtown.” From there, teams ideate a wide range of fixes (app-based ride sharing, dedicated bus lanes, flexible work hours, etc.) and build quick, low-fidelity prototypes (pilot mobile apps or mock-ups). Finally, you test with real users and learn: did our solution actually reduce wait times or fare hassles? Then you refine and repeat. Crucially, the steps – Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, Test – form a cycle, not a one-off checklist.

In government services, this mindset can be transformative. The Harvard Ash Center notes that design thinking encourages us to “listen, prototype, and act with citizens at the center,” rather than imposing top-down fixes. For example, instead of assuming “Karachi has a traffic problem so build more roads,” authorities might first interview daily commuters about their pain points, sketch a model of the journey, and test whether a re-timed traffic light or a new bus route actually relieves stress. Pakistan has already seen promising pilots: civic tech groups have used design thinking to improve surveys and service kiosks. Imagine expanding this: suppose Lahore’s traffic engineers took actual journey-time data (say, from hundreds of GPS-tracked trips) and then shadowed drivers on peak hours. They might discover the true bottleneck is not on the main highway but at a certain intersection. Then they could prototype an AI signal there (even using open-source tools), test it overnight, and measure the delay reduction, all before committing billions to a flyover.

Design thinking also forces us to tackle the human side of data. It would have our transit agencies ask, “What stops people from using our data-driven services?” and solve those obstacles. Perhaps an app exists that tells subway crowding, but older citizens can’t use it, the fix might be a simpler SMS alert system. Or a traffic-monitoring dashboard might be published, but without public awareness it fails to change commuter choices so we’d iterate on better outreach or incentives. In Pakistan’s context, critics note that bureaucratic inertia is our biggest hurdle: policies change in top-down silos, and services often miss the mark. Design thinking’s emphasis on collaboration, prototyping and feedback breaks down those silos. It encourages pilots (even at small scale) and cross-agency teams. Internationally, governments have used HCD (human-centered design) to simplify complex forms, streamline apps, and dramatically increase uptake of public programs. We need a similar transformation: Pakistani officials, planners and tech professionals learning to experiment with data-driven tools under the guidance of citizen feedback, rather than finalizing massive infrastructure by decree.

Toward Smarter Cities and Safer Communities

What does the future hold if Pakistan adopts these approaches? Plenty of hope. Even today, smartphones in Pakistani hands carry the seeds of big data: anonymized movement patterns, mobile-payment trails and crowd-sourced feedback. If urban planners tapped into this responsibly, they could map demand hotspots in real time. Coupled with the design thinking ethos, that data could spawn citizen-friendly solutions. Imagine a Lahore app that not only shows metro schedules, but lets passengers vote on extra train services when they see crushes forming. Or a Karachi traffic control room that actually adjusts lights based on live congestion metrics, a trial of which could be prototyped and refined using local traffic data. Health clinics and hospitals could use analytics to predict patient surges, then prototype telemedicine services during peak seasons (iterating based on actual use). Our e-government portals could be rebuilt through user testing, turning the cold data of drop-off rates into fresh, intuitive designs.

Most importantly, a data-enabled design approach can rebuild public trust. When citizens see their input lead to tangible changes, confidence in government grows. And Pakistan’s young tech talent can play a starring role, building the smart solutions and data models needed, guided by the empathy of design thinking. The barriers like legacy mindsets, fragmented agencies, resource limits are real. But the examples of Beijing and Singapore show it is possible to put millions of people’s movements, pattern of their choices and decisions onto a screen and let smart algorithms find efficiencies every day. Pakistan’s fast growing citiescan leapfrog many stages: by starting data collection now and fostering a culture of human-centered experimentation, learning from the global best practices and adapting them in the local context and needs.

The lesson is clear: data gives us insight into what is happening in our cities; design thinking helps us figure out what to do about it. If Pakistan can embrace both, wiring up our services with technology and engaging communities at every step of the way, we can dramatically improve our urban services. We can build systems that grow and adapt in real time, rather than stagnating under outdated plans. The story of smart Beijing is still unfolding, but its early chapters already teach us that smart-city isn’t just fancy gadgets; it’s a way of listening to data and to people, together. With the right mindset, Pakistan’s next generation of planners and technologists can write the next chapter in a sustainable manner.