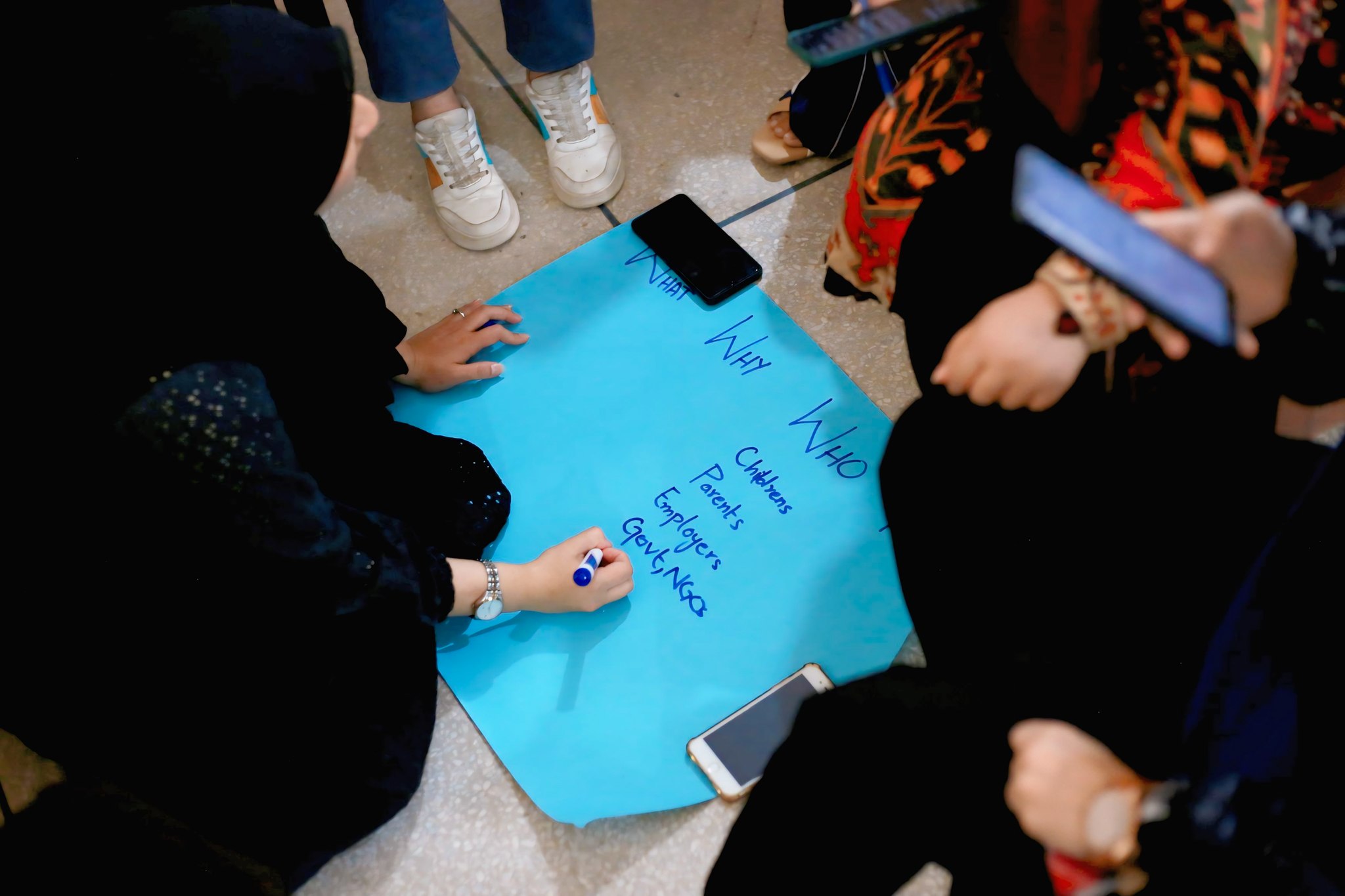

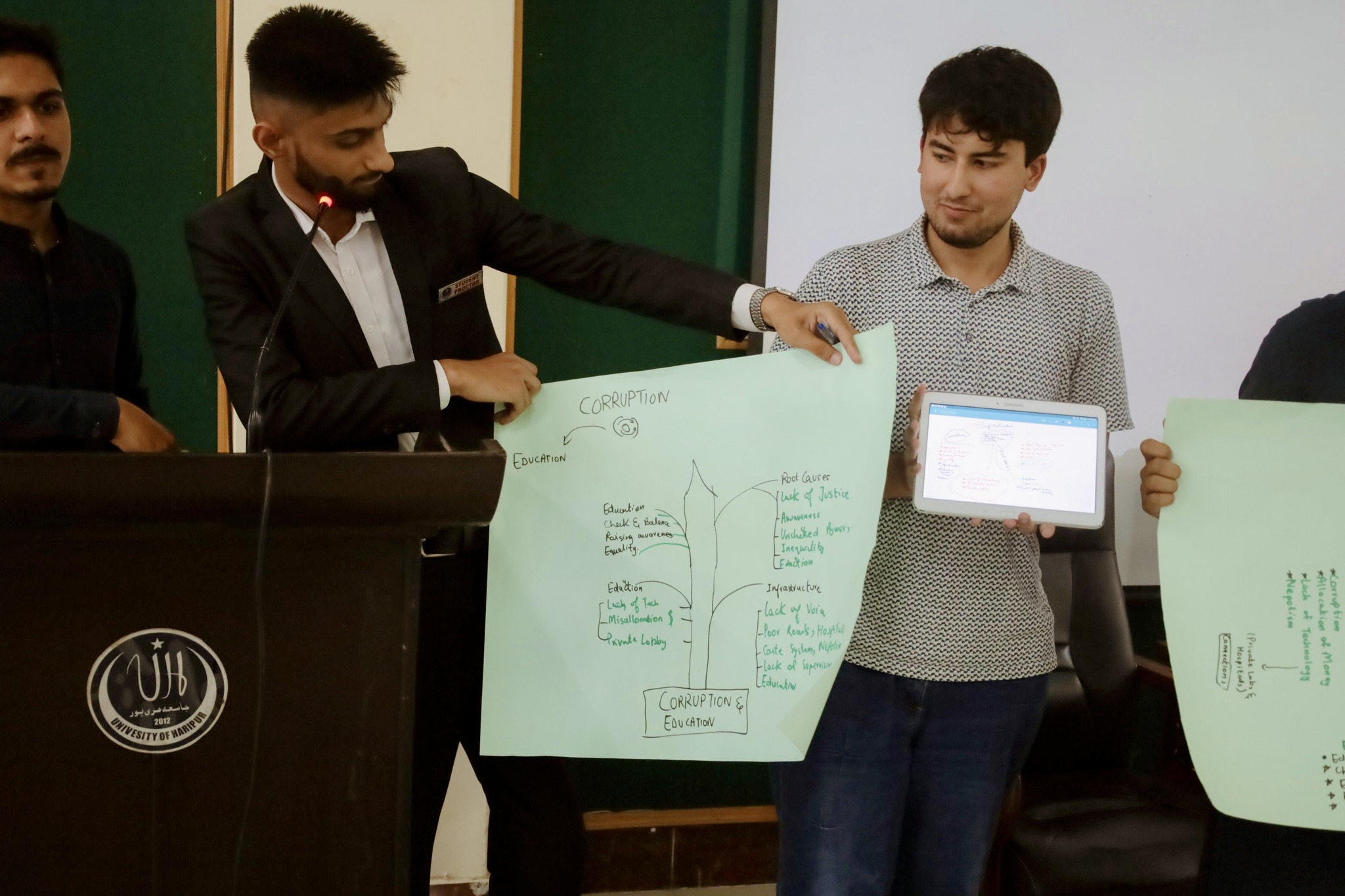

Farq Parhta Hai is a strategically designed youth engagement initiative that places university students at the forefront of countering violent extremism (CVE) in Pakistan. Supported by the European Union in Pakistan and implemented by Accountability Lab Pakistan in collaboration with NACTA and UNODC Pakistan, the project engages students from five partner institutions: International Islamic University Islamabad, Rawalpindi Women University, University of Haripur, Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, and Mehran University of Engineering and Technology Khairpur Mir’s. Recognizing that young people are often both targets and potential disruptors of extremist narratives, the initiative adopts a multi-pronged approach that builds critical thinking, empathy, and local leadership.

The project unfolded through a structured format comprising orientation sessions, panel discussions, two-day training workshops, and the development of social action plans, referred to as youth-led projects. It also incorporated a virtual media competition, a series of podcasts featuring CVE experts, and online discussions, all designed to amplify messages of tolerance and inclusion through digital platforms. By targeting universities in high-risk or underserved regions, Farq Parhta Hai strengthens grassroots resilience while connecting local realities to broader national and international efforts. The initiative shifts the CVE paradigm from reactive, top-down strategies to proactive, youth-driven solutions grounded in context, creativity, and collaboration.

Radicalization, Identity and the Power of Grassroots Dialogue

Insights from “Farq Parhta Hai” with Dr. Amir Raza

In this episode of the Farq Parhta Hai podcast, Dr. Amir Raza helps listeners understand radicalization beyond the headlines. The goal is not to provoke fear, but to create understanding. Dr. Raza, a Fulbright scholar and experienced academic, speaks from both lived experience and deep research. His approach is honest, clear, and refreshingly direct.

What is Radicalization?

According to Dr. Raza, radicalization is part of a larger spectrum. It begins with the belief that gradual change is not possible, and that drastic or revolutionary action is needed to fix a broken system. This belief is called radicalism.

Extremism, the next step, comes in when someone feels the need to impose these ideas on others. Violent extremism is when a person believes that using force to push these ideas is justified. These concepts are often confused or used interchangeably, but Dr. Raza emphasizes that we need to understand them as stages that build on one another.

Radicalization is a Global Issue

One of the most powerful points made in this episode is that radicalization is not just a Pakistani problem. It is happening around the world in different forms.

Dr. Raza points to examples from the United States, such as white supremacist groups that rose alongside political movements like the Tea Party or Trumpism. He mentions Anders Breivik in Norway, who killed dozens of children because of fears tied to white replacement theory. In India, radicalization takes a different shape under the ideology of Hindutva, which has increasingly targeted Muslims.

These examples show that radicalization thrives in environments where fear, hate, and identity politics are encouraged.

How Pakistan’s History Shaped Today’s Problems

Turning to Pakistan, Dr. Raza explains how history and policy decisions have contributed to the current situation. During the Afghan war of the 1980s, religious identity was used to motivate people for jihad. This created a fertile ground for radical thinking that was never fully addressed afterward.

He also talks about ungoverned or semi-governed spaces, places like the former FATA regions that were politically neglected and underdeveloped. These areas lacked infrastructure, opportunity, and connection with the rest of the country, which made them more vulnerable to ideological influence. Many people across Pakistan did not even see these regions as part of their shared reality, allowing radical ideas to grow unchecked.

The Identity Crisis Among Youth

Perhaps the most insightful part of the discussion is about the identity crisis facing Pakistan’s youth. Dr. Raza says the problem is not just economic. Many countries are poorer but face less radicalization.

In Pakistan, young people are confused about who they are. Are they Muslims first, or Pakistanis? Should they identify with their ethnic group, their sect, or their nation? This confusion stems from mixed messaging in textbooks, media, and public discourse. Without a clear, inclusive identity, it is easy for people to feel lost and to be drawn toward radical or extremist views.

The State’s Response: Some Steps Forward, Many Steps Missing

Dr. Raza acknowledges that the state now sees radicalization as a real challenge. Programs like Paigham-e-Pakistan, NACTA, and the National Action Plan were positive steps. But the real problem is follow-through. Efforts are often reactive instead of long-term. There is little focus on changing mindsets, improving education, or addressing the identity confusion that fuels radical thinking. The state is caught up in emergency responses, putting out fires without planning how to prevent new ones. Dr. Raza also points out that when the state tries to confront radical groups, it sometimes backs down out of fear of political backlash. Without strong intellectual and moral clarity, policies lose their strength.

Real Change Starts from Below

Despite these challenges, Dr. Raza offers hope. He believes that true transformation comes from grassroots conversations. When people talk to each other, ask questions, and listen with openness, real progress happens. He shares stories of students who once rejected ideas like pluralism, calling them part of a foreign agenda. After engaging in open dialogue and education, those same students began leading study circles and promoting peace in their communities. These are the kinds of stories that matter. They show that change is possible when people are given space to think, reflect, and connect.

Conversation is Contagious

Dr. Raza ends on a powerful note. Just like a disease can spread, so can ideas. When you engage in meaningful conversation, you influence others. Critical thinking is contagious, and it can lead to powerful shifts in perspective. He reminds us not to wait for change to come from leaders or institutions. It starts with ordinary people. It starts with conversations like the one in this podcast. And most importantly, it starts with believing that our voices matter.

The title of the podcast, Farq Parhta Hai, means “It Makes a Difference.” And this episode is a clear reminder that even small conversations, when rooted in empathy and understanding, truly can make a lasting difference.

Peace Begins with Inclusion

Key Lessons from Podcast with Romana Bashir

Education as a Site of Division, Not Connection

One of the most significant contributors to radicalization, Romana argued, is the education system itself. From an early age, children are exposed to a curriculum that reinforces religious divisions. Where once children were unaware or indifferent to religious identities, now even primary school students differentiate between Shia, Sunni, Christian, and Hindu peers. Romana noted that textbooks and teaching practices have shifted over the last forty years to normalize exclusion rather than inclusion. Teachers, having been trained in the same system, often perpetuate harmful narratives in their classrooms. In this context, both students and educators lack the tools to navigate religious diversity with sensitivity and respect.

Missed Opportunities in Religious Leadership

Religious leaders hold immense influence, especially in communities where formal education is lacking or mistrusted. Friday sermons and public religious discourse have the potential to foster interfaith understanding. However, Romana emphasized that many of these opportunities are lost when leaders promote exclusivity and criticize other faiths without nuance or context. The pulpit could serve as a powerful tool for unity, but its current misuse reinforces division and often isolates religious minorities further. Without exposure to genuine interfaith dialogue, people rely on secondhand and often biased narratives.

Women’s Inclusion: A Critical Missing Link

Romana identified women’s exclusion from decision-making as another root of societal imbalance. From household decisions to national policies, women are often left on the margins. This exclusion is not just cultural but institutional. She observed that women, even when economically active, often have limited control over their income or mobility. She linked this exclusion to broader peacebuilding efforts, stating that meaningful change cannot occur without women’s leadership at every level. Her organization has worked to ensure women are included in community dialogue groups, where their perspectives bring empathy, practicality, and often a higher degree of social sensitivity. Romana shared a powerful example in which women led a peaceful intervention at a police station to defend a domestic worker falsely accused of theft. Their leadership was instrumental not just in resolving the conflict but in humanizing the process for all involved.

Normalizing Interfaith Engagement

Romana’s work includes organizing interfaith visits to places of worship and promoting cultural gatherings where communities share meals, music, and conversation. These interventions are rooted in the belief that people fear what they do not know. Familiarity, she argued, is the first step toward dismantling prejudice. One such initiative involved taking Muslim religious scholars to Nankana Sahib, where they engaged in open dialogue with Sikh leaders. Many came away realizing they had misunderstood the faith entirely. These efforts help reduce not just misinformation but also the emotional distance between communities.

Structural Exclusion of Religious Minorities in Politics

Perhaps the most sobering aspect of Romana’s analysis was her critique of political structures. Reserved seats for minorities in Pakistan’s assemblies have not increased since the 1980s, even as the overall number of seats has expanded. This signals a regression in representation, not progress. Romana drew attention to the multiple layers of marginalization faced by non-Muslim women, who are underrepresented even within the already limited pool of reserved seats. Their absence from political spaces means critical decisions are made without their input, including those that directly affect their safety and rights. She recalled the passage of a clause barring non-Muslims from becoming Prime Minister in 2010, a change made without a single minority representative in the room. Such examples highlight how systemic exclusion leads to laws and policies that entrench inequality.

Persistent, Grounded, and Inclusive Work

Romana’s closing message was clear. Peacebuilding cannot rely solely on top-down policy reforms or isolated campaigns. It requires persistent, patient, and inclusive work at the community level. She underscored the need for dialogue that begins in classrooms, homes, places of worship, and neighborhoods, rather than waiting for change to be handed down from political or institutional elites. In her words, “We work for humans. Every effort that tries to divide people—on the basis of religion, gender, or class—must be countered.” Her model of inclusion is not abstract or performative. It is deeply human, practical, and rooted in lived experience.

Romana Bashir’s work reminds us that building peace is not about grand statements. It is about who is present in the room, who gets to speak, and whether all people, especially those at the margins are heard.

Critical Thinking and Countering Extremism in Pakistan

Insights from “Farq Parhta Hai” with Dr. Zafar Iqbal

Why Education is Central to Preventing Extremism

In this episode of Farq Parhta Hai, Dr. Zafar Iqbal, a seasoned academic and former Dean at International Islamic University, shares his perspective on how education can either prevent or contribute to the spread of violent extremism in Pakistan. He points out that while many initiatives exist under the label of “awareness,” they don’t go far enough. Seminars, walks, poster competitions, and campaigns can inform people that extremism exists, but they don’t address why it takes root in the first place.

Extremism Has Many Faces

Dr. Zafar emphasizes that extremism in Pakistan is not limited to religion. It appears in various forms such as ethnic, linguistic, sectarian, racial, and political extremism. He says these forms of extremism differ from one region to another. For example, what drives frustration or violence in Gilgit-Baltistan may be very different from what fuels radicalization in Balochistan or Punjab. Yet, we often try to apply the same solutions to every region, without understanding the root causes. He urges for a diagnostic approach that treats each form of extremism with its specific history and social context.

The Crisis of Critical Thinking

One of the most powerful points made in the conversation is about the absence of critical thinking in Pakistan’s education system. According to Dr. Zafar, real learning begins when students are allowed to question what they’re taught. Unfortunately, in many classrooms, especially at the university level, students are expected to accept and memorize ideas rather than challenge them. He points out that some topics, figures, and ideologies are placed beyond critique, which kills the very foundation of critical thinking.

Classrooms Without Dialogue

Dr. Zafar paints a clear picture of how university classrooms are often monologues. A teacher comes in, lectures for hours, and leaves. There is no space for students to ask questions, argue, or explore ideas. He stresses that the learning process must be dialogic, where thoughts are not only presented but also tested, challenged, and improved through discussion. Without this environment, students cannot become independent thinkers.

Teachers Are Not Trained to Teach

Another major issue, he says, is the way teachers are hired. In most cases, having an academic degree is enough to begin teaching. However, teaching is more than delivering content. It involves developing students’ minds, asking the right questions, guiding discussions, and identifying early signs of problematic thinking. But since teachers themselves are not trained in these areas, they often fail to cultivate critical, open-minded students.

The Damage of Commercialized Education

Dr. Zafar also criticizes how universities have become businesses. The focus is now on student numbers rather than quality education. Classrooms are overcrowded, and teachers are expected to handle large groups without any real engagement. This model leaves students without depth, without critical skills, and more vulnerable to manipulation from outside sources, especially online platforms.

Social Media Fills the Void

In the absence of meaningful dialogue in schools and universities, young people turn to social media to find answers or express their frustrations. Unfortunately, social media is full of hate speech, propaganda, and divisive content. If students had proper spaces within the education system to share their thoughts and learn to engage respectfully, many of them would never fall into these traps. Dr. Zafar believes that classrooms must serve as buffers against harmful ideologies, not just lecture halls.

What Should Be Done

When asked about concrete solutions, Dr. Zafar lays out a clear roadmap. First, we must understand the difference between preventing extremism and simply reacting to it. Prevention means identifying vulnerabilities early and building resilience. Second, he says we need region-specific analysis. Each area and social group has its own set of challenges, and we need tailored strategies for each. Third, the curriculum must be revised to avoid glorifying violence and instead focus on moderation, coexistence, and empathy. Fourth, he insists on the need for dialogue forums at every educational level so that students can learn to engage critically and respectfully.

Every Stakeholder Has a Role

Dr. Zafar makes it clear that change cannot come from one direction. Teachers, parents, institutions, media, and the state all have a role to play. The biggest responsibility lies with the education system. If classrooms continue to promote passive learning, the problem of radicalization will continue to grow. But if we take steps to foster debate, encourage questions, and support open thinking, we can build a generation that is much harder to mislead.

Challenge the Idea, Not the Person

To close the conversation, Dr. Zafar shares a simple but powerful message. Every issue has more than one side. We must make it a habit to listen to alternate views and consider them with an open mind. Speaking without understanding both sides of a story is unjust, and injustice is at the root of many extremist beliefs. He encourages students, teachers, and communities to keep asking, keep listening, and keep thinking.

This podcast reminds us that education is not just about facts. It is about forming minds that are aware, thoughtful, and resilient. And that kind of education makes all the difference.

Faith, Tolerance and the Power of Real Dialogue in Pakistan

Insights from “Farq Parhta Hai” with Ghulam Murtaza

What Interfaith Really Means

A major takeaway from this episode is Murtaza’s effort to explain what interfaith dialogue actually is. Many people assume that interfaith efforts aim to merge religions or challenge individual beliefs. In truth, interfaith is not about changing anyone’s religion. It is about ethics, social behavior, and how we treat others as human beings. Murtaza emphasizes that all religions teach values like kindness, compassion, and the importance of looking after our neighbors. Interfaith work focuses on these shared values. Whether someone prays five times a day or follows different customs, that is their personal path. What matters most is how they behave toward others in society.

The Gap Between Beliefs and Actions

Even though all major religions promote peace, our behavior often does not match these teachings. Murtaza calls attention to this growing disconnect. He notes that people speak of unity but practice division. This contradiction becomes especially clear when people face discrimination based on their faith. He believes the solution starts with a focus on tarbiyat, or moral training. We often focus on academic content in schools, but not enough on how to treat others. Murtaza encourages schools and colleges to help students think critically, understand different perspectives, and learn how to communicate with respect.

Trust and Openness are Key

From his experience and research, Murtaza offers practical steps for anyone working toward interfaith harmony. The most important one is building trust. This means being clear about your goals and making sure people feel safe and respected during dialogue. Another important step is approaching every conversation with an open mind. People often carry strong assumptions about others, especially those from different religious or ethnic backgrounds. But real understanding starts when we set aside those assumptions and truly listen. Murtaza shares how scriptural reasoning, a method where people explore common values in religious texts, helped groups find shared meaning. This helped break down barriers and allowed people to connect on a deeper level. He also talks about the value of exposure. For example, he helped create opportunities for madrasa students and university professors to learn from each other. This kind of interaction helped both groups move past stereotypes and understand each other’s worldviews.

Engaging the Youth with Purpose

Since most of Pakistan’s population is under the age of 30, Murtaza believes engaging youth is one of the most urgent tasks we face. Today’s young people are constantly receiving religious messages through social media. Some of these messages come from groups that promote conflict and division. To counter this, Murtaza says we need to teach critical thinking skills and encourage questions. Instead of blindly accepting and forwarding information, young people need tools to verify what they see and hear. He also points out that youth today are missing opportunities to express themselves culturally and artistically. In the past, village festivals brought people together, but many of those traditions have disappeared. Bringing back cultural events could help young people feel more connected to their communities and less drawn to extreme ideologies.

Moving Toward Acceptance

One of the most powerful ideas Murtaza shares is the difference between three mindsets: exclusivism, inclusivism, and pluralism. Exclusivism says only one group is right and everyone else is wrong. Inclusivism says others might be right too and deserve to be heard. Pluralism goes further and says that everyone’s identity, opinion, and culture are equally valuable. He believes that Pakistani society is still moving from exclusivism to inclusivism. We are not fully at the point of pluralism yet, but the journey has started. Understanding where we are can help us move forward.

Stories that Inspire

Toward the end of the podcast, Murtaza shares stories that show how faith can bring people together. One story from Nigeria is especially moving. A Muslim Imam and a Christian Pastor, who once led opposing groups during violent conflict, later came together to create the Interfaith Mediation Center. Their journey from enemies to peacebuilders is a reminder that change is possible when we truly embrace the values of our faith. He also highlights lesser-known heroes in Pakistan, such as Zahida Umaid, a woman in a wheelchair who started a factory to employ others with disabilities. Another example is a woman from Swat who became the first female member of a traditional Jirga. These stories rarely get attention, but they show the power of courage and inclusion.

Final Thoughts

This podcast reminds us that peacebuilding does not require huge resources or powerful positions. It can begin with small efforts, honest conversations, and a willingness to listen. As Murtaza says, one person choosing to focus on tolerance, respect, and dialogue can set off a chain reaction that reaches far beyond their own circle. Pakistan has a long history of different communities living together peacefully. Those traditions still exist, and they can guide us today. Whether you are a student, teacher, parent, or community leader, you have a role to play in shaping a more compassionate and united society.

Let us move forward together, not by denying our differences, but by honoring them. Peace is possible when we choose understanding over judgment and dialogue over silence.

Women, Education and Peacebuilding in Pakistan

Insights from “Farq Parhta Hai” with Dr. Faryal Razzaq

Why Women Matter in Peacebuilding

In this powerful episode of Farq Parhta Hai, Dr. Faryal joins the conversation to explore how women can play a transformative role in building peace and preventing extremism in Pakistan. As a researcher, consultant, and expert in emotional intelligence, her perspective brings together data, experience, and a deep understanding of gender dynamics in our society. She opens by challenging the way peacebuilding is traditionally understood. It’s often thought of as something that belongs to governments or militaries. But Dr. Faryal argues that if we look closely, women are not only directly impacted by violence, they are also in a unique position to prevent it at home, in classrooms, and in communities. Yet they remain largely excluded from peace processes.

The Numbers Tell a Harsh Story

Despite making up half the population, women are severely underrepresented in global and national peace efforts. Globally, only 2 percent of peace mediators are women, and only 9 percent participate in negotiations. In Pakistan, the statistics are even more alarming. The country ranks 141st in gender parity, and even lower in economic and educational indicators. Research shows that when women are involved, peace agreements are 35 percent more likely to last. More female representation in parliament also leads to less international conflict. So the question is not why women should be involved, but why they are being left out.

The Classroom Problem: Educators and Extremism

One of the most shocking moments in the podcast is when Dr. Faryal shares findings from her research on university faculty. The results showed that nearly 70 percent of faculty members held violent views, over 30 percent exhibited extremist tendencies, and more than 80 percent showed impulsive, high-risk behavior. These are the same people teaching the next generation. The problem isn’t limited to religious seminaries—many educators in mainstream universities also harbor these views.

If the teachers themselves are not emotionally and ideologically balanced, how can we expect students to develop healthy perspectives? Dr. Faryal emphasizes the need to screen educators and provide training that includes emotional intelligence and ethical reasoning.

Mothers Raise the Nation

The role of mothers in shaping values is just as critical. According to research, 60 percent of a person’s values are formed at home. But what happens when mothers themselves are emotionally unwell or financially dependent? When young boys are taught to be the protectors of their mothers, it not only burdens the child but also reinforces harmful gender roles. Dr. Faryal shares a telling anecdote: a man who refused to let his wife work because it was “dishonorable,” while he worked for a woman himself. This kind of selective thinking reveals how deeply patriarchy is ingrained in our society. To raise emotionally stable children, mothers need emotional security and financial independence. Without these, the cycle of inequality and instability continues.

What Girls Are Taught (And What They’re Not)

Another major insight is the way boys and girls are raised differently from the very start. Boys are encouraged to make decisions, like choosing things in the market, while girls are rarely allowed to practice decision-making. This early gap has long-term consequences—girls grow up hesitant and uncertain, simply because they were never trained to trust their own judgment. Even in higher education, women face hidden challenges. A recent study by Dr. Faryal found that most women who reached leadership roles in academia were unmarried or divorced, suggesting that to succeed, many had to sacrifice family life. This points to a need for systems that support women without forcing them to choose between career and personal life.

Start With the Children

So how do we change this? According to Dr. Faryal, the most powerful place to begin is early education. She led a project that used cartoon-based video programs to teach children about emotional resilience, personal space, and bullying. Instead of using heavy terms like “sexual violence,” the program introduced concepts like “my space bubble” to make children aware of boundaries. The results were stunning. In just six weeks, behavioral improvements were seen in nearly all the children. Even more concerning, about 40 percent of children reported having experienced some form of abuse. This shows that children are not just passive observers. They are living these realities and we need to give them the language and tools to understand what is right and wrong.

Education Is More Than Academics

Another key takeaway is that education should not be limited to academic subjects. Dr. Faryal calls for emotional intelligence and ethics to be taught as core subjects from Montessori through university. She shares examples from the Center for Ethical Leadership, where they introduced a “Character and Good Manners” program and embedded ethics modules into accounting and economics. This isn’t just about making better students, it’s about making better human beings.

The Real Roadblocks

So what’s stopping all this from becoming reality? A combination of factors: deeply rooted patriarchy, systemic corruption, lack of teacher training, and inconsistent implementation of even the most progressive policies. Government initiatives exist, but if the person at the police station or university is biased, those policies mean nothing. Until these systems are fixed from within, women’s empowerment will remain a slogan, not a lived reality.

Final Thoughts

Dr. Faryal ends with a clear message. Women must be involved in peacebuilding, not just as a token but as key decision-makers. It is not enough to celebrate women on certain days or include them in panels for optics. Real empowerment begins with education, emotional security, and financial independence.

This episode is a reminder that peace begins at home, in classrooms, in conversations between parents and children, and in the everyday choices we make. And if we want a peaceful Pakistan, we need to start by building emotionally resilient, empowered women.

Why Countering Extremism in Pakistan Requires More Than Just Policy

Insights from “Farq Parhta Hai” with Amir Rana

In a recent episode of Farq Parhta Hai, leading security analyst and peace researcher Amir Rana joined host Momna Sahar for a thought-provoking discussion on violent extremism in Pakistan. The conversation explored where the state is going wrong, how the public is reacting, and what needs to change if long-term peace is to become a reality.

More Policies, Less Progress

Amir Rana began by outlining a troubling reality. Since 2007, Pakistan has introduced more than a dozen policies aimed at countering extremism. These include the well-known National Action Plan, the National Internal Security Policy, and the newer National Policy on Prevention of Extremism. While these frameworks have clear goals, most of them have never been fully implemented. Rana explained that the real issue is not the lack of written policy but the absence of commitment and follow-through. He emphasized that despite having these documents, extremism in Pakistan has continued to grow, shift, and evolve. The state, meanwhile, has failed to remain consistently engaged or responsive to the root causes.

Moving Beyond Poverty as the Default Explanation

One of the most commonly cited causes of extremism is poverty. Rana challenged this narrative, pointing to newer research from Pakistan and other countries. While poverty and unemployment can make individuals vulnerable, the deeper issue is often about identity, dignity, and recognition. People who feel unheard, unseen, or wronged by the state are more likely to become frustrated, angry, and eventually radicalized. In Pakistan, the transition from lower-income groups to a struggling middle class has created new pressures. When individuals feel that their lives are stagnant or that they are excluded from opportunities, the emotional response can be severe. Extremism, in this context, becomes a form of protest against injustice and marginalization.

Disconnection Between State and Society

Rana spoke at length about the growing distance between Pakistan’s governing institutions and its citizens. The political elite is divided, and that division is reflected throughout society. People no longer trust the state to deliver, to listen, or to protect. As a result, communities are disconnected from national efforts to counter extremism. He also pointed out the contradiction in how religious institutions are handled. The state continues to support and empower madrasa graduates by placing them in public teaching roles, yet also expects them to play a role in fighting extremism. According to Rana, this conservative mindset does not directly cause terrorism, but it remains incompatible with modern worldviews, making genuine reform difficult.

The Social Media Paradox

The rise of social media has added a new layer to the extremism challenge. Platforms can be tools for education and connection, but they also spread radical ideologies. Rana criticized the government’s tendency to respond with surveillance and censorship, arguing that this only deepens the mistrust between citizens and the state. Young people use their phones not only for entertainment but also for identity formation. Rana stressed that instead of trying to control their behavior, the government should be listening to their concerns and helping them navigate the digital world responsibly.

Civil Society Has Untapped Power

Despite many obstacles, Rana remained optimistic about the role of civil society. Across Pakistan, there are local initiatives that support peace, education, and community health. Organizations like Edhi and Fatimid are clear examples of what is possible when people come together with purpose and integrity. However, these efforts receive little institutional support. Most charitable giving still goes directly to religious institutions, often as a way to avoid taxes. As a result, grassroots organizations struggle for funding and recognition, even though they are often the ones doing the most impactful work on the ground.

The Role of Youth

Pakistan’s youth make up a large portion of its population, yet they remain confused and unsupported. Rana explained that young people are willing to contribute, but they lack clear direction. While there are youth-led clubs, literary circles, and sports groups across the country, most operate without any backing from the government or formal institutions. For youth engagement to become effective, the state needs to invest in platforms that allow young people to express themselves, learn leadership skills, and connect with others. This is not just about funding events or campaigns, but about building a system that recognizes the potential of young people as change-makers.

Why Inclusivity in Policy Matters

Perhaps the most powerful critique in the conversation came when Rana addressed how policies are created. He argued that most are drafted behind closed doors, with little input from communities, educators, or experts outside of Islamabad. Calling a few meetings or showing slides in a presentation does not count as inclusion. Real inclusivity requires actively seeking out diverse voices, understanding cultural dynamics, and building policies that reflect the needs of different regions and social groups. According to Rana, this process should be led by parliament, not left entirely to bureaucrats. Only then can policies gain legitimacy and public trust.

Final Thoughts

Amir Rana’s insights serve as a reminder that tackling extremism is not just about issuing statements or launching new programs. It requires empathy, genuine dialogue, and collaboration between state institutions and the people they serve. Policies alone will not bring change unless they are rooted in trust, inclusion, and a deeper understanding of what truly drives radicalization.

To move forward, Pakistan needs to recognize the value of its youth, listen to its citizens, and support the grassroots organizations already working to make a difference. Only then will counter-extremism efforts lead to meaningful and lasting change.

Building Bridges in Divided Times

Lessons from Israr Madani’s Journey of Peacebuilding

In today’s world, where division and extremism often dominate headlines, the story of Dr. Israr Madani stands out as a powerful reminder of what can be achieved through empathy, dialogue, and persistence. A peacebuilder, author, and founder of the International Research Council for Religious Affairs (IRCRA), Madani joined the Farq Padhta Hai podcast to reflect on his journey and the lessons he has learned along the way.

A Shift in Perspective

Madani grew up in a politically charged environment after 9/11, where literature, education, and conversation were filled with emotionally driven narratives. Immersed in this worldview, he pursued traditional religious studies through Dars-e-Nizami. However, as he moved through his education, his perspectives gradually began to change. A turning point came in 2009 when he attended an inter-sect workshop for the first time. This experience exposed him to people he had only ever read about. It surprised him to realize that these individuals, from different sects and backgrounds, shared many of the same concerns. They cared deeply about Pakistan, about youth, and about the future. This encounter laid the foundation for his lifelong commitment to understanding others and building peace through dialogue.

Faith as a Tool for Healing

One of Madani’s most influential efforts began after a major setback in public health. When the CIA used a fake polio campaign as part of a covert operation, trust in health workers plummeted. Many were viewed with suspicion, and violence against vaccination teams escalated. Madani responded by opening quiet, respectful conversations with religious leaders. Instead of confronting them with controversy, he began by asking simple but profound questions about Islamic teachings on the health of mothers and children. This approach allowed scholars to engage without defensiveness, and eventually led to widespread support for vaccination efforts. Major religious institutions including Dar-ul-Uloom Haqqania and Jamia Farooqia joined the conversation, releasing endorsements and public messages. These efforts grew into the National Islamic Advisory Group and then expanded into an international network supported by religious leaders from Egypt and Saudi Arabia. What began as a local initiative became a model for global religious diplomacy.

Resolving Conflict Through Unity

Madani also highlighted several moments when religious scholars helped resolve deep-rooted tensions in Pakistan. One significant example was the sectarian violence of the 1990s, when clashes between Sunni and Shia groups had become widespread. During this crisis, a group of scholars formed the Milli Yakjehti Council and, through dialogue and consensus, developed a Code of Ethics. This agreement significantly reduced violence and is still considered one of the most effective efforts in Pakistan’s recent history. It showed that religious leadership, when rooted in sincerity and cooperation, can accomplish what state mechanisms sometimes cannot. Another more recent example was the Paigham-e-Pakistan initiative, where more than 1,800 scholars signed a unified declaration against extremism. This document helped clarify the constitutional boundaries of religious discourse and was widely accepted by religious and social organizations across the country.

Rethinking Peacebuilding

Madani believes peacebuilding is often misunderstood as something only for elites who attend conferences or earn international fellowships. In reality, he says, peace begins at home. It lives in how people speak to each other, how they resolve conflict in their neighborhoods, and how they listen across differences. To help make this vision more accessible, he launched creative programs like the Madrasa-University Cricket League. The idea was simple. Instead of debating ideology, students from madrasas and universities would come together to play cricket. These games were paired with sessions on identity, dialogue, and conflict transformation. The events included people from various sects and even minority communities. Despite the competitive setting, all 23 matches were conducted peacefully, without a single conflict or outburst. It was a powerful example of unity through shared experience.

A Message for Young Peacebuilders

To young people interested in peacebuilding, Madani offers clear guidance. Start where you are. Get to know the local forums that already exist whether they are jirgas, neighborhood committees, or religious councils. Many of these spaces are already engaged in peace efforts, even if they don’t carry that label. He also encourages youth to apply for fellowships like the Azadi Fellowship, which trains participants to understand both local and global conflict. These programs are open to people from all educational backgrounds and often lead to deeper engagement with international networks. Madani emphasizes the need to internationalize Pakistan’s success stories, particularly since the global narrative tends to focus only on conflict and crisis. One example he shared was a visit to Japan, where Pakistani scholars learned lessons about cleanliness, classroom culture, and student leadership. Those who traveled returned home with practical ideas that improved their own institutions, proving that exposure to new environments can spark meaningful change.

The Power of Listening

Madani ended the conversation with a simple but powerful message. Before forming an opinion about someone, take time to understand them. Whether the issue is political, religious, or social, empathy is essential. Once understanding is in place, disagreement becomes less threatening and more respectful.

His story is a testament to the power of conversation and the importance of starting small. True peacebuilding does not require fame or funding. It requires intention, patience, and a willingness to listen. These are the tools that helped Israr Madani transform from a student of traditional religious thought into a globally recognized peacebuilder—and they are tools that all of us can use.

Media, Mindsets, and the Mission to Counter Extremism in Pakistan

Podcast Insights from Talha Ahad and Nouman Manzoor Podcast

In an age where algorithms reward outrage and misinformation spreads faster than truth, the role of media in peacebuilding is more important than ever. In a powerful episode of Farq Padhta Hai, host Momina Sahar sat down with two experts who are at the forefront of countering violent extremism through storytelling and communication. The guests included Talha Ahad, CEO and founder of The Centrum Media (TCM), and Noman Manzoor, a communications strategist with deep experience in peacebuilding and media literacy. Their discussion explored how digital media can either reinforce polarization or become a tool for promoting understanding, empathy, and long-term social change.

Rethinking the Purpose of Media

Talha Ahad opened the conversation by reflecting on the origins of TCM. From the beginning, the goal was clear. The platform was not built to chase viral trends but to offer balanced narratives, especially for young audiences. Talha emphasized three founding principles: tackle misinformation, provide accessible storytelling through video, and amplify voices that often go unheard. This approach, he explained, was not about avoiding tough topics. It was about presenting them in a way that felt real and responsible.

Why Sensationalism Wins and What We Can Do About It

Noman Manzoor added that media professionals must understand the psychology behind what draws people in. Negative content, especially when it’s dramatic or shocking, tends to get more attention. This creates a major challenge for those trying to spread positive narratives. Stories about peace, interfaith harmony, and social cohesion exist—but they rarely go viral. He pointed out that even something as simple as this podcast creates ripples. Each conversation plants seeds. With time and consistency, positive narratives can grow.

Journalism in the Digital Age

The conversation then shifted to the evolving role of journalism in the digital space. Talha highlighted a worrying trend: digital news creators, unlike those in traditional media, often operate without editorial oversight. Content is published rapidly, and thumbnails are often misleading. Once a video is online, it stays there—regardless of whether it was accurate or ethical. This permanence, he stressed, increases the need for self-accountability. Journalists, vloggers, and content creators must think not just about engagement, but about the long-term consequences of their work.

Campaigns That Work Start With Content That Connects

Noman explained that in the world of peacebuilding, converting cause-driven content into something people want to watch is an uphill task. Many campaigns struggle to break through the noise. He gave the example of the drama Tan Man Neel o Neel, which subtly addressed mob violence and social divisions. By weaving in critical messages through relatable storytelling, the drama succeeded where lectures or press releases often fail. His takeaway was simple. The gap between content creators and development professionals needs to shrink. When storytellers and peacebuilders work together, the result is content that educates without alienating.

Storytelling Is More Than Strategy—It’s a Responsibility

Both guests agreed that storytelling plays a crucial role in shifting mindsets. Talha noted that the most impactful content at TCM often features ordinary people sharing their experiences. By humanizing abstract issues, audiences begin to relate. Boring topics can become compelling if they are told through real stories. This approach is especially effective on social media, where attention spans are short and emotions drive engagement. Rather than forcing an agenda, storytelling allows the message to land naturally.

Training the Youth to Think Critically

A key part of the discussion focused on youth and their role in consuming and creating content. Noman argued that Pakistan’s younger generation is often lost in digital noise, with few real-world opportunities for expression. Without early lessons in empathy, emotional intelligence, and critical thinking, many fall into the trap of blindly accepting what they see online. He stressed the importance of caregivers, especially women, in identifying behavioral changes and fostering awareness. Teachers, mothers, and mentors all have a role to play in raising media-literate citizens who can spot harmful narratives before they take root. Talha added that content creators need to understand the weight of their influence. There are no formal rules or university courses for online content creation, so personal ethics and accountability become even more important. Every video or post should be treated as something that may live forever and possibly shape the thinking of future generations.

Conscious Consumption Is Just As Important

Momina then flipped the question to the audience. What responsibility do viewers have? Talha responded by emphasizing the importance of digital literacy. Today’s kids are growing up with phones, not football fields. Instead of restricting access, we need to teach them how to assess content thoughtfully. A simple pause to ask, “Is this accurate?” can make a difference. Noman encouraged people to look for alternative perspectives. If one video presents a strong opinion, find another that challenges it. Reality is often found somewhere in between. Trusting only what’s trending can lead to echo chambers that distort public understanding.

The Algorithm Is Ruthless

Momina raised the issue of rage bait—content designed to provoke strong reactions to gain visibility. Talha acknowledged the challenge of competing with sensationalism. While responsible content may not always go viral, it still needs to be interesting and relatable. Otherwise, important messages will be ignored. At TCM, they strive to strike a balance. The team experiments with formats, uses voiceovers, and even explores AI-generated visuals to keep audiences engaged while staying true to their mission.

Final Takeaways for Young Creators and Consumers

As the podcast drew to a close, both guests shared words of advice. Talha encouraged content creators to act with more awareness. Every time you publish or share something, think about its potential impact. Noman reminded listeners not to believe everything they see online. Algorithms are powerful, but so is critical thinking. Ultimately, the message of the podcast was clear. We all have a role to play in shaping the media landscape. Whether you’re a journalist, a student, or just someone scrolling through your feed, your choices matter.

Reimagining Peace

Lessons from Ali Hameed’s Journey with Shaoor Foundation

In a world that often feels overwhelmed by conflict, extremism, and disconnection, stories like that of Ali Hameed offer a rare glimpse into what it means to lead with integrity, clarity, and hope. As the founding chairperson of the Shaoor Foundation, Hameed brings over 14 years of experience in peacebuilding, civic education, and community engagement. In his conversation with Farq Padhta Hai, he reflects on the events that shaped his path, the communities that influenced his thinking, and the advice he holds for young people striving to create change.

A Turning Point in a Year of Chaos

Hameed’s journey toward peacebuilding began not in a classroom or training but amidst a national crisis. The year 2007, marked by the Lal Masjid operation, political emergency, the rise of extremism, and the assassination of Benazir Bhutto, left a profound impact on him. As a young university student studying engineering in Islamabad, he was already attuned to current affairs. These events forced him to question the responsibilities that come with privilege the access to education, safety, and political awareness and whether that privilege demanded more than just passive observation. What began as a spark of awareness evolved into a deeper inquiry. Concepts like democracy, the social contract, and constitutional responsibility, which were often recited without context in schoolbooks, suddenly took on real meaning. Hameed found himself driven to understand the system he lived within, and to empower others to do the same.

The Birth of Shaoor

That sense of urgency led to the creation of the Shaoor Society a student-led peace movement initially operating within university spaces. Despite being in a university with strict boundaries around political discourse, Hameed and his peers carved out space for dialogue, organizing social events and speaker sessions. Eventually, the movement grew beyond the confines of one campus and in 2012 formally evolved into the Shaoor Foundation for Education and Innovation. Even today, the roots of that original initiative live on in campus clubs, continuing to shape new waves of young changemakers.

Starting Small, Staying True

As the conversation shifted to advice for aspiring youth activists, Hameed emphasized the importance of authenticity. He spoke of how initiatives often fail when they are launched only to follow trends or appear relevant. Instead, he encouraged listeners to find work that truly resonates with their personal values. Because when someone is genuinely passionate, they’re more likely to persist through setbacks, confusion, and criticism. This process, he explained, isn’t about immediately launching a startup or NGO. It starts with awareness, a personal SWOT analysis, and exposure to existing spaces. Whether through volunteering, internships, or simply showing up it’s in these small steps that long-term impact begins to take root. He also reminded listeners that comparing one’s journey to someone else’s can be misleading. Every path unfolds at its own pace, and progress looks different for everyone.

Finding Strength in Vulnerability

Over the years, Hameed has encountered many powerful moments that reshaped his understanding of peace. One such memory that stayed with him was a protest by the Hazara community, where grieving families held the bodies of their loved ones in freezing temperatures. What struck him wasn’t just the tragedy, but the immense strength and dignity with which these communities continued to advocate for peace even in moments of unimaginable pain. He explained that peacebuilding isn’t just a political ideal or strategy it’s a lived ethic. To choose nonviolence in moments of extreme vulnerability is the truest test of conviction.

Unexpected Allies

Through his work, Hameed also came to challenge many assumptions about institutional partnerships. While civil society often distances itself from state institutions or religious seminaries, he found surprising openness when he reached out. Institutions like the National Counter Terrorism Authority (NACTA) and the National Assembly offered constructive engagement. Religious seminaries often viewed with suspicion turned out to be welcoming and eager to collaborate, spanning all major sects and regions. These experiences reinforced the idea that many barriers are imagined built more on hesitation and fear than actual rejection. When approached with respect and clarity, even the most unexpected actors can become partners in peace.

The Salamti Fellowship: A Model for Youth Peacebuilding

Among all his projects, the Salamti Fellowship remains closest to Hameed’s heart. Designed as a residential program to build youth capacity in preventing violent extremism, Salamti has now run 13 successful cohorts. It brings together young people from across the country and equips them with tools ranging from academic sessions to meditation and experiential learning.

What makes it special, Hameed noted, is not just the content but the community it creates. Salamti alumni can be found in every corner of Pakistan, continuing the work in their own cities and contexts. The fellowship serves as a fast-track to finding like-minded allies something that often takes years when working alone.

Resilience in the Face of Disappointment

Of course, no journey is without setbacks. Hameed acknowledged that not every plan comes to life. Ideas fail. Collaborators disappear. Promises are broken. But in those moments, he finds grounding by returning to the core questions: Why did I begin this journey? What values drive me? These reflections serve as reminders that progress isn’t always visible or immediate and that even small wins matter. Hope, he believes, isn’t a passive emotion. It’s a discipline, a mindset built through faith, patience, and daily recommitment.

A Call to Empathy

As the conversation came to a close, Hameed offered a final message rooted in empathy both for others and for oneself. He recognized the hopelessness many young people feel today and encouraged them to channel even a small part of that into action. Whether in the realm of environment, gender, or poverty, each person holds the power to make a difference within their own circle.

He urged listeners not to wait for perfect conditions or widespread praise. Instead, he reminded them to keep showing up, even when it feels thankless and to hold on to the belief that what they’re doing matters. Because in a world in need of healing, even the smallest act of sincerity can become a source of transformation.

Challenging Extremism from the Ground Up

Musarrat Qadeem’s Vision for Sustainable Peace

In the global conversation on preventing violent extremism, local voices are often drowned out by top-down narratives. Yet it is within communities themselves that real, lasting change must begin. In a recent episode of the Farq Padhta Hai podcast, peacebuilder and pioneer Musarrat Qadeem, co-founder and Executive Director of Paiman Alumni Trust, offered a deeply grounded reflection on her work, shaped by over 18 years of experience navigating complex social dynamics, cultural sensitivities, and ideological divides in Pakistan.

Understanding the Real Root Causes

Much of the global discourse around violent extremism tends to center poverty, illiteracy, and social deprivation as root causes. Musarrat challenges this idea. While these factors are certainly present in many affected regions, they have long existed in communities that remained peaceful. What, then, catalyzed the rise of extremism? According to her, the real issue is not merely poverty or ignorance it is exploitation. Extremist ideologies often find entry points through trusted local influencers who strategically manipulate grievances, religious texts, and existing social divides. These instigators are calculated, charismatic, and deeply familiar with the communities they target. It is their ability to embed themselves in the emotional and ideological gaps within a society that transforms local discontent into radicalization.

Religion Misunderstood, Narratives Unchallenged

One of the most dangerous gaps that extremists exploit, Qadeem notes, is the widespread lack of contextual understanding of religious texts. For many Pakistanis, Arabic is not a first language, and religious teachings are often received without translation or interpretation. This opens the door for selective narratives particularly around concepts like jihad to be weaponized. Without access to the full theological and historical context, individuals internalize a distorted vision of faith, often without even realizing it. This distortion, she argues, is not adequately challenged by the state or civil society. The absence of a clear, grounded counter-narrative has allowed extremist ideologies to flourish unchecked. In many cases, communities have lacked both the knowledge and the tools to question what is being taught or spread in their name.

From Countering to Preventing: A Shift in Strategy

Musarrat is careful to distinguish between countering violent extremism and preventing it. While the former implies reacting to an already existing threat, prevention requires a more proactive, holistic approach. It means creating resilient communities where extremist ideologies struggle to take root in the first place. Her model emphasizes building both vertical and horizontal networks connecting grassroots communities with trusted leaders and broader institutions. Through education, dialogue, and inclusion, she believes communities can be empowered not just to detect early signs of radicalization, but to respond meaningfully and effectively to them.

Empowerment Begins with Trust

Paiman’s approach to peacebuilding is deeply embedded in local contexts. From linguistic familiarity to cultural sensitivity, Musarrat stresses the importance of “being one of them” of understanding a community’s pain, identity, and lived experiences. Imported agendas and outsider-driven programs, no matter how well-intentioned, are rarely welcomed unless they resonate with the community’s own sense of ownership. Paiman’s work includes developing community peace structures, engaging trusted local voices, and creating environments where dialogue and healing are possible. Contrary to common assumptions, she emphasizes that madrasas are not the sole breeding grounds for radicalization. In fact, the majority of radicalized youth encountered in her work came from general communities. This highlights the need for peace education not just in religious spaces, but across all educational institutions.

Creating Indigenous Alternatives

For Musarrat, the response to extremism isn’t just about countering narratives it’s about offering alternatives. Economic empowerment, access to education, and social inclusion are critical. Equally important is theological clarity: explaining what jihad actually means in Islamic jurisprudence, and who has the authority to declare it. By reclaiming these narratives and grounding them in truth, communities can begin to dismantle the myths that extremists propagate. Paiman’s model is not reactive it is indigenous and preventative. It is built by those who have lived through radicalization and now work to stop others from following the same path. These transformed individuals have become peace leaders, resolving local disputes, preventing outbreaks of violence, and rebuilding the social fabric from within.

Peace That Grows From Within

Sustainable peacebuilding, according to Musarrat, cannot be achieved through superficial gestures. Holding sports tournaments or symbolic events may foster temporary unity, but without addressing the root drivers and engaging radicalized individuals directly, these efforts fall short. True prevention involves recognizing early signs, engaging meaningfully, and helping individuals understand the harm caused by radical ideologies to themselves, their families, and their communities. The work is not easy. It demands emotional endurance, personal risk, and a clarity of purpose. But when done right, its impact ripples outward, transforming not only individuals but entire neighborhoods. Paiman has already prevented numerous violent incidents and resolved hundreds of community-level disputes through mediation and trust-building.

From Resistance to Resilience

One of the recurring challenges in peacebuilding, Musarrat explains, is the suspicion often faced by those associated with international organizations. In communities scarred by conflict, foreign agendas are rarely trusted. This is why authenticity is essential. Speaking the community’s language literally and metaphorically is the only way to be accepted and effective.

Paiman has succeeded in bringing women out of their homes and into leadership roles in regions where that was once unthinkable. This progress was made possible not through confrontation, but through deep cultural understanding and sustained engagement. Their work is not merely gender-responsive it is gender-focused, actively reshaping norms in some of the country’s most conservative regions.

Where Can Youth Begin?

For young people inspired by this work, Musarrat’s advice is simple yet powerful: be vigilant, seek knowledge, and stay engaged. Extremist ideologies seep into communities quietly and often unnoticed until it’s too late. Awareness is the first step. Youth must take responsibility for educating themselves, questioning the narratives they encounter, and dedicating time to learning, not just scrolling.

Platforms like Paiman offer opportunities for involvement, but meaningful change begins with individual intent. Whether through community service, peace education, or counter-narrative development, youth can play a vital role in steering their communities away from division and toward dignity.

Peace as a Collective Responsibility

Musarrat Qadeem’s journey is not one of slogans or symbolic victories. It is a story of showing up day after day in the most challenging spaces, and doing the hard work of listening, educating, and healing. Her approach reminds us that peace is not imposed from above. It grows from within communities, through people who are empowered to protect and preserve it.